Following on from our earlier posts (Australia has no time to waste in implementing crowd funding and Is crowd funding an alternative means for raising capital?) on crowd-sourced equity funding (CSEF), it is good to see that Treasury has recently released its discussion paper for further consultation.

Crowd-sourced Equity Funding – Discussion Paper, December 2014

Treasury has recognised that CSEF may present an important source of additional funding to promote innovation and productivity growth, particularly for small businesses and start-ups. Treasury also notes (as previously suggested by CAMAC) that the current regulatory requirements present a barrier to the widespread use of CSEF in Australia.

Although a final decision has not been made on the preferred CSEF framework for Australia, Treasury is seeking feedback on potential CSEF models (and respective advantages and disadvantages of such models), including the model recommended by CAMAC in July 2014 reviewed in our last post, and the model that has recently been implemented in New Zealand which came into force in April 2014. The discussion paper includes a useful comparison between these different models, such as the differing approach to individual investor caps. The paper also provides an overview of considerations if the status quo is maintained.

The closing date for submissions is 6 February 2015 and we will be considering our responses, as well as any responses received from our clients, to the questions that have been raised by Treasury.

Tuesday 23 December 2014

Tuesday 9 December 2014

Publish what you pay: Australia's proposed mandatory anti-corruption reporting standards

In an attempt to eradicate bribery and corruption in the extractives industry, governments around the world, including the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom are introducing mandatory reporting requirements to increase revenue transparency and accountability for resource extraction companies.

The Corporations Amendment (Publish What You Pay) Bill 2014 (Cth) (Bill) sets the stage for Australia to formally align its governance standards with those of its closest allies. If passed, it will require Australian-based extractives companies to report payments they make to governments on a country-by-country, project-by-project basis.

The introduction of the Bill is consistent with Australia’s pilot of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global benchmark which supports improved governance in resource-rich countries through the full publication and verification of payments to governments.

‘Reportable payments’ (including payments in kind) are broadly defined by the Bill and capture production entitlements, taxes, royalties, dividends, signing, discovery or production bonuses, licence fees, infrastructure improvements, social payments (e.g. payments relating to or given for community projects) and payments for security services.

To avoid concealment of smaller payments, the proposed Bill treats a series of related payments that together meet the threshold of AUD$100,000 as a single payment.

To comply with the reporting requirements, companies will be required to lodge an annual report with ASIC for each resource extraction project that the company is engaged in and for each government entity that the company makes a reportable payment to. The specific details and rules surrounding the reporting requirements, however, are yet to be finalised.

The proposed legislation requires ASIC to make the company report available, free of charge, on its website not longer than 28 days after receiving it.

The Corporations Amendment (Publish What You Pay) Bill 2014 (Cth) (Bill) sets the stage for Australia to formally align its governance standards with those of its closest allies. If passed, it will require Australian-based extractives companies to report payments they make to governments on a country-by-country, project-by-project basis.

The introduction of the Bill is consistent with Australia’s pilot of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global benchmark which supports improved governance in resource-rich countries through the full publication and verification of payments to governments.

Who is affected?

The proposed legislation creates new mandatory reporting requirements for all ASX-listed companies, unlisted public companies, large proprietary limited companies, and controlled joint venture companies that are engaged in a resource extraction activity. For the purposes of the Bill, ‘resource extraction activities’ include the following activities in relation to oil, gas, mineral mining and native forest logging:- exploration

- prospecting

- discovery

- development, and

- extraction or logging.

What must be reported?

If the Bill is introduced, affected companies will be required to report any payment, or series of payments, of more than AUD$100,000 made to a domestic or foreign government (including an authority of, or a company owned by, that government entity) in relation to a resource extraction activity.‘Reportable payments’ (including payments in kind) are broadly defined by the Bill and capture production entitlements, taxes, royalties, dividends, signing, discovery or production bonuses, licence fees, infrastructure improvements, social payments (e.g. payments relating to or given for community projects) and payments for security services.

To avoid concealment of smaller payments, the proposed Bill treats a series of related payments that together meet the threshold of AUD$100,000 as a single payment.

To comply with the reporting requirements, companies will be required to lodge an annual report with ASIC for each resource extraction project that the company is engaged in and for each government entity that the company makes a reportable payment to. The specific details and rules surrounding the reporting requirements, however, are yet to be finalised.

The proposed legislation requires ASIC to make the company report available, free of charge, on its website not longer than 28 days after receiving it.

Penalties

A failure to take all reasonable steps to comply with or to secure compliance with these new financial reporting requirements will constitute a breach of the Chapter 2M of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and will be subject to the civil penalty provisions of the Act.Key takeaway

As a result of the heightened scrutiny of payments to governments globally, including with the proposed introduction of the Bill, Australian extractives companies should take a closer look at their existing anti-corruption policies and procedures to review their effectiveness.Monday 10 November 2014

Ten tips for AGM season

With the AGM season in full swing, we felt it was timely to highlight some key considerations in the lead up to, and when conducting, your AGM.

While for many, conducting an AGM is a straight-forward process, there are times when contentious issues arise. Set out below are ten tips for managing an effective AGM, and strategies for dealing with anticipated and unexpected issues.

Finally, this year has illustrated the ongoing importance of engaging with institutions and their proxy advisers. This is often left too late and can result in adverse ‘strikes’ on the remuneration report or votes against director re-elections. Post-AGM may be a good time to review any proxy patterns and the quieter time between AGM seasons more conducive to constructive discussion.

While for many, conducting an AGM is a straight-forward process, there are times when contentious issues arise. Set out below are ten tips for managing an effective AGM, and strategies for dealing with anticipated and unexpected issues.

1. Be prepared

By now the location and timing of the meeting will be set (see our earlier post: Time to start thinking about your AGM), but the preparations for the AGM will be ongoing. In addition to addresses from the chairman and CEO, this may include preparing a chairman’s script for the formal part of the meeting and considering responses to key questions that may be asked of directors and management, and potentially the auditor. Hot topics this year include:- board performance and review processes

- excessive remuneration

- independence of directors - including long standing directors, substantial shareholders or those who have commercial dealings with the company, and

- effective contribution of directors who hold multiple board roles.

2. Review your meeting procedures

In addition to a refresher on some of the relevant provisions of the constitution; it is worth reviewing some of the general commentaries on procedures for conducting the meeting. For example, the ‘rules of debate’ or procedural motions (see Chapter 11 of The Chairman’s Red Book) can greatly assist in managing questions and discussion at the AGM.3. Get to the point

The ‘point of order’ is a particularly useful tool for alerting the chairman to a matter requiring their attention or correction during the AGM. It takes precedence over the discussion taking place and must be ruled on by the chairman immediately. For example, alerting the chairman to a reference to a special resolution which is actually an ordinary resolution.4. Take the AGM notice as read

It is generally no longer necessary to ask a shareholder to move a resolution and ask another to second the motion. At the beginning of the meeting the chairman should confirm their intention to ‘take the notice as read (unless shareholders object)’. This assists to streamline the consideration of resolutions.5. Understand the voting exclusions

Understand the voting exclusions that apply to each resolution under the Corporations Act, the Listing Rules (if applicable) and, potentially, the company’s constitution. This is likely to be particularly important for the remuneration report (for a listed company) and other remuneration-related resolutions. The chairman should be advised and understand who are the ‘key management personnel’ in the room excluded from voting on such resolutions.6. Plan for spills

The remuneration report – although now a familiar process for many in the listed environment, for companies that may face a ‘second strike’ at the AGM, processes should be in place for considering and voting on a spill resolution at the AGM.7. Disclose proxies

Monitor and disclose proxies as an early warning signal of a potentially contentious item of business. Disclosure of proxy results (e.g. on a PowerPoint) can also assist in reducing protracted debate in the room (e.g. if it is clear that the proxies are overwhelmingly in favour). This may also include engagement with voters in the lead up to the AGM, such as if the usual participants have not returned their proxies. At the same time, knowing who is in the room is also vital, with voting more commonly conducted on a show of hands at the AGM.8. Be prepared for a poll

For listed companies and large unlisted companies, your share registry should be on hand to assist with a poll, but it is also good for the chairman to understand when it is best for a poll to be called and the key steps involved in the process (e.g. the requirement for an adjournment for the poll to be counted). The timing of the poll is often essential to ensure that shareholder engagement is maintained.9. Consider the timing of questions

This may include taking questions as each resolution is considered, during or after the addresses of the chairman and CEO, and/or deferring to the end of the meeting. Although shareholders as a whole should be given a reasonable opportunity to participate and ask questions at the meeting, the chairman should be wary of a shareholder that seeks to dominate proceedings and know when to bring an end to discussions or limit the number of questions. A useful method can be to refer a shareholder to appropriate board members or executives for further clarification following close of the meeting.10. Consider your compliance requirements

For listed companies, ensure any presentations or addresses are released prior to the start of the meeting and the results of the AGM made available as soon as practicable following the close of the meeting.Finally, this year has illustrated the ongoing importance of engaging with institutions and their proxy advisers. This is often left too late and can result in adverse ‘strikes’ on the remuneration report or votes against director re-elections. Post-AGM may be a good time to review any proxy patterns and the quieter time between AGM seasons more conducive to constructive discussion.

Tuesday 9 September 2014

Honest and reasonable…or irresponsible?

A proposed new defence for company directors

The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) has recently proposed a new ‘honest and reasonable director defence’ for inclusion in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act). The new broad based defence would apply to all contraventions of the Corporations and ASIC Acts, significantly expanding the scope of protections currently afforded to directors.

The proposal has been met with criticism from both ASIC and certain shareholder groups, concerned with a defence which they argue potentially goes too far in protecting directors that may not have been acting responsibly.

The impetus for change

The ‘business judgment rule’ defence in section 180(2) of the Corporations Act, introduced in 1998, has a relatively narrow scope. Importantly, the defence only applies to a director’s statutory duty of care and diligence under section 180(1) and the equivalent common law and equitable duties. It is not available, for example, to directors who are charged with insolvent trading or the duty to act in good faith and the best interests of the company. The rule is also limited to positive business judgment decisions and so is not seen to cover a breach arising from an omission by a director, such as in the Centro litigation in 2011.The AICD proposal highlights what are, in its view, a number of negative consequences of the limited existing protections. Its surveys have revealed significant concerns among directors about the risk of personal liability that has prompted an overly conservative approach to business decisions, creating a negative shift in the directors’ role away from governance and toward technical compliance. Such an approach leads to problems in making forward looking statements and responding to corporate insolvency, the latter often causing directors to place potentially profitable companies too quickly into external administration. The AICD also identifies the lack of protection for directors as a key reason for the reluctance of strong candidates to take on directorships.

The ‘honest and reasonable director defence’

The AICD’s proposed solution to the above issues is to introduce a new catch-all defence to liability where a director acts:- honestly

- for a proper purpose, and

- with the degree of care and diligence that the director rationally believes to be reasonable in the circumstances.

The defence would apply to all provisions of the Corporations and ASIC Acts (and their common law and equitable equivalents), not just the duty of care and diligence.

The AICD has suggested that this would also apply to strict liability provisions. This is potentially difficult to reconcile, as having regard to the subjective state of mind of the person that breached such a provision goes against the nature of strict liability (which ignores the director’s intention). Some example strict liability provisions are the duty to disclose material personal interests (section 191), to not vote on resolutions in which a director has a material personal interest (section 195) and the duty to disclose directors’ remuneration (section 202B). Any application to strict liability offences will need to be carefully considered. A broader issue is the seemingly increasing tendency for strict liability to be applied to statutory drafting as a default.

The defence extends to omissions as well as positive acts, which was considered by many to be a key failing of the existing business judgment rule.

This aspect of the defence could potentially improve directors’ access to the protections in a manner consistent with the Corporations Act without overly compromising the position of shareholders.

The defence includes a subjective test – that a director rationally believes their action (or inaction) was reasonable in the circumstances.

By contrast, the business judgment rule provides that the director’s judgment must be rational ‘unless the belief is one that no reasonable person in their position would hold.’ This is an important distinction, allowing for a broad range of potential arguments based on the surrounding (potentially high pressure) commercial circumstances at the time the decision was made, rather than by reference to an objective standard. Concerns with this subjective element are valid and it is this aspect of any new defence which is likely to be subject to the greatest scrutiny.

The AICD has raised important issues with the proposed new defence, which has been met by concerns from ASIC and certain shareholder groups. As is always the case when dealing with directors’ duties and protecting shareholder (and other stakeholder) interests, it is a balancing act which, if a new defence is developed, will need to strike a mid-point between the views of each group.

Monday 18 August 2014

Australia has no time to waste in implementing crowd funding

There have been a number of recent updates since our last blog on ‘crowd funding’ worthy of note. In particular, release of the 245 page CAMAC report on crowd sourced equity funding (CSEF), being CAMAC’s last report prior to its abolition and transfer of its functions to Treasury.

With Australian law (particularly the Corporations Act) not yet accommodating crowd funding, it remains to be seen whether Australia can keep pace with the new regulatory regimes being implemented internationally to accommodate this new and evolving concept of raising capital.

The CAMAC report set out a blueprint for the new regulatory structure required to overcome current legal impediments for issuers and implement regulations required for intermediaries of crowd funding websites, at the same time as maintaining necessary protections for retail investors.

The report considered four options for implementing CSEF in Australia:

Some of the key aspects of the new regime proposed by CAMAC are as follows:

The CAMAC report also considered initiatives in other overseas jurisdictions in some detail. In doing so, CAMAC recognised that there is likely to be a benefit of having a level of international harmonisation in managing CSEF, given the cross jurisdictional nature of CSEF offers being made online.

The key international comparisons were as follows:

As can be seen, there is much common ground between New Zealand, Canada and the USA, and CAMAC’s proposals for Australia.

With two crowd funding platforms in New Zealand (PledgeMe and Snowball Effect) now fully licensed under the NZ Financial Markets Conducts Act 2013 (since 31 July 2014), Australia should be mindful not to fall behind international peers in determining its approach to CSEF.

Inhibiting CSEF in Australia, while others move to implement it, may result in Australian crowd funders moving offshore, with New Zealand in particular appearing to have the first mover advantage.

Though certainly not without risks for retail investors, CSEF could emerge as an important alternative means of raising capital. It therefore needs to be managed and implemented appropriately by a legal framework specifically designed for the task, balancing the interests of retail investors at the same time as assisting to address the ‘capital gap’ for many start-up and smaller companies in Australia.

A response is expected from Treasury later this year.

With Australian law (particularly the Corporations Act) not yet accommodating crowd funding, it remains to be seen whether Australia can keep pace with the new regulatory regimes being implemented internationally to accommodate this new and evolving concept of raising capital.

CAMAC recommendations

The CAMAC report set out a blueprint for the new regulatory structure required to overcome current legal impediments for issuers and implement regulations required for intermediaries of crowd funding websites, at the same time as maintaining necessary protections for retail investors.

The report considered four options for implementing CSEF in Australia:

- adjusting the regulatory structure for proprietary companies

- confine CSEF offers to a limited class of investors

- amending the fundraising provisions for public companies, and

- introducing a regulatory regime specifically designed for CSEF.

Some of the key aspects of the new regime proposed by CAMAC are as follows:

For issuers

- The introduction of a new corporate entity – an exempt public company – with the status of a public company, but with reduced compliance requirements (e.g. no AGM, no audited financial reports if within certain financial thresholds), together with an ability for a pre-existing entity to convert to ‘exempt’ status.

- A standard disclosure template – to include details on the entity, offer, terms of shares, related party shareholdings, business plan and proposed use of funds – but which is not required to be lodged with ASIC.

- Issuer cap – no more than $2 million in any 12 month period (but no cap on the number of investors).

- Offer limited to one class of share at any particular time (but does not prevent having alternative classes – e.g. founder shares).

- Share re-sale restrictions only apply to directors / other associates of the issuer.

For intermediaries

- Requirement to have a CSEF licence (issued by ASIC).

- Requirement to undertake limited due diligence on the issuer and its management.

- Requirement to issue standard form risk disclosure statement.

- Need to implement appropriate dispute resolution processes.

- Offer may only be made via one licensed intermediary.

- No financial advice - e.g. ‘staff picks’ or ‘what’s hot’.

- No lending to investor.

- No participation in offer – need to avoid conflicts of interest.

- Disclosure of fees required.

For investors

- Non-binding investment caps for any twelve month period, of no more than $2,500 per CSEF issuer and no more than $10,000 for all issuers, with requirement for investor to self-certify that they are in compliance with the caps.

- Requirement for investor to sign acknowledgement of risk prior to investing.

- Cooling-off period – e.g. right to withdraw within 5 business days of investment.

Progress by international peers

The CAMAC report also considered initiatives in other overseas jurisdictions in some detail. In doing so, CAMAC recognised that there is likely to be a benefit of having a level of international harmonisation in managing CSEF, given the cross jurisdictional nature of CSEF offers being made online.

The key international comparisons were as follows:

New Zealand

New Zealand implemented its crowd funding regime in April 2014 via the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 and Financial Markets Conduct (Phase 1) Regulations 2014. The new regime allows for applications to be made to the Financial Markets Authority to be licensed as a ‘crowd funding service’. Issuers through this service are exempt from the requirement to register a disclosure document for the offer. A major distinction from CAMAC’s recommendations is that there are no investment caps (although the issuer cap of $2 million in 12 months applies). At this stage New Zealand CSEF offers do not qualify for mutual recognition in Australia.UK

Since April 2012, the UK has allowed for CSEF offers to be made to restricted classes of investors (e.g. sophisticated investors, investors receiving qualifying investment advice, and investors that certify they will not invest more than 10% of their portfolio in CSEF type investments).Canada

Although still at the proposals stage, and with different regimes likely to be implemented in each region of Canada, it is anticipated that a similar approach will be taken to CAMAC’s proposal for Australia.USA

The introduction of Jumpstart our Business Startups (JOBS) Act 2012, allows issuers to raise $1 million in 12 months through an online intermediary with a maximum individual investment of $100,000. However, CSEF in the USA will not begin until the SEC has settled its rules on CSEF.As can be seen, there is much common ground between New Zealand, Canada and the USA, and CAMAC’s proposals for Australia.

No time to waste

With two crowd funding platforms in New Zealand (PledgeMe and Snowball Effect) now fully licensed under the NZ Financial Markets Conducts Act 2013 (since 31 July 2014), Australia should be mindful not to fall behind international peers in determining its approach to CSEF.

Inhibiting CSEF in Australia, while others move to implement it, may result in Australian crowd funders moving offshore, with New Zealand in particular appearing to have the first mover advantage.

Though certainly not without risks for retail investors, CSEF could emerge as an important alternative means of raising capital. It therefore needs to be managed and implemented appropriately by a legal framework specifically designed for the task, balancing the interests of retail investors at the same time as assisting to address the ‘capital gap’ for many start-up and smaller companies in Australia.

A response is expected from Treasury later this year.

Friday 18 July 2014

Blogs: protecting your business from damaging posts

The Federal Court of Australia has handed down a valuable decision for business owners concerned their business reputation is being damaged by a competitor’s misleading online blog posts.

The decision of Nextra Australia Pty Limited v Fletcher [2014] FCA 399 establishes that, in certain circumstances, the posting of a misleading online blog article regarding a business competitor can amount to conduct which is prohibited under the Australian Consumer Law. With recent reports indicating there are now more than 150 million blogs in existence, the decision is a timely reminder for those operating a blog for commercial reasons.

The applicant in the case, Nextra, is the franchisor of a newsagency franchise operating throughout Australia. The respondent, Mr Fletcher is a director and 50% shareholder of NewsXpress, another newsagency franchise system, and competitor of the Nextra franchise. Mr Fletcher operates an internet blog under the name ‘Australian Newsagency Blog’. On 27 April 2011, Mr Fletcher posted an article on the Blog entitled ‘Nasty campaign from Nextra misleads newsagents’ (Article), and referred to a flyer which had been distributed in print form by Nextra.

After publication of the Article, Nextra commenced proceedings seeking orders that the Article be removed from the blog, that Mr Fletcher be restrained from publishing the Article in any other form and that Mr Fletcher publish a retraction of the Article with an apology to Nextra.

To succeed in its case, Nextra was required to satisfy the Court that the contents of the Article were ‘misleading and deceptive’, and that the posting of the Article occurred ‘in trade or commerce’.

The Court concluded that the Article published by Mr Fletcher, when viewed as a whole, would leave a reasonable reader with the impression that Nextra had distributed false information in its promotional campaign. The evidence was that Nextra had not, in fact, distributed false information in its promotional campaign.

As to whether the posting of the Article occurred ‘in trade or commerce’, Mr Fletcher submitted the Article was merely published in a public forum for matters affecting the newsagency industry. The Court dismissed this submission and instead found that Mr Fletcher had sought to promote his own commercial interests in posting the Article.

Accordingly, the Court found that the posting of the Article was done with an inherently commercial motive which gave the conduct the requisite commercial character.

The Court ultimately ordered that Mr Fletcher remove the Article from the blog and be restrained from publishing the Article in any other form. In so ordering, the Court remarked that readers of the Article would be misled to form erroneous and negative conclusions about Nextra and added that it was in the public interest for such misleading and deceptive material to be removed from the public forum.

Readers should note that the mere publication of an article should not, of itself, be seen as constituting conduct ‘in trade or commerce’. Importantly, as in the Nextra case, the particular blog or forum on which the article is published must be one where its owner seeks to promote its own commercial interests.

Often a misleading or deceptive blog article (whether in stock forums, private blogs or Facebook posts) can be simply and inexpensively removed or retracted through directed legal correspondence with the blog’s owner or the service provider. If this approach is not successful, remedies such as those used in the Nextra case may also be available to affected business owners.

The decision of Nextra Australia Pty Limited v Fletcher [2014] FCA 399 establishes that, in certain circumstances, the posting of a misleading online blog article regarding a business competitor can amount to conduct which is prohibited under the Australian Consumer Law. With recent reports indicating there are now more than 150 million blogs in existence, the decision is a timely reminder for those operating a blog for commercial reasons.

The applicant in the case, Nextra, is the franchisor of a newsagency franchise operating throughout Australia. The respondent, Mr Fletcher is a director and 50% shareholder of NewsXpress, another newsagency franchise system, and competitor of the Nextra franchise. Mr Fletcher operates an internet blog under the name ‘Australian Newsagency Blog’. On 27 April 2011, Mr Fletcher posted an article on the Blog entitled ‘Nasty campaign from Nextra misleads newsagents’ (Article), and referred to a flyer which had been distributed in print form by Nextra.

After publication of the Article, Nextra commenced proceedings seeking orders that the Article be removed from the blog, that Mr Fletcher be restrained from publishing the Article in any other form and that Mr Fletcher publish a retraction of the Article with an apology to Nextra.

To succeed in its case, Nextra was required to satisfy the Court that the contents of the Article were ‘misleading and deceptive’, and that the posting of the Article occurred ‘in trade or commerce’.

The Court concluded that the Article published by Mr Fletcher, when viewed as a whole, would leave a reasonable reader with the impression that Nextra had distributed false information in its promotional campaign. The evidence was that Nextra had not, in fact, distributed false information in its promotional campaign.

As to whether the posting of the Article occurred ‘in trade or commerce’, Mr Fletcher submitted the Article was merely published in a public forum for matters affecting the newsagency industry. The Court dismissed this submission and instead found that Mr Fletcher had sought to promote his own commercial interests in posting the Article.

Accordingly, the Court found that the posting of the Article was done with an inherently commercial motive which gave the conduct the requisite commercial character.

The Court ultimately ordered that Mr Fletcher remove the Article from the blog and be restrained from publishing the Article in any other form. In so ordering, the Court remarked that readers of the Article would be misled to form erroneous and negative conclusions about Nextra and added that it was in the public interest for such misleading and deceptive material to be removed from the public forum.

Readers should note that the mere publication of an article should not, of itself, be seen as constituting conduct ‘in trade or commerce’. Importantly, as in the Nextra case, the particular blog or forum on which the article is published must be one where its owner seeks to promote its own commercial interests.

Often a misleading or deceptive blog article (whether in stock forums, private blogs or Facebook posts) can be simply and inexpensively removed or retracted through directed legal correspondence with the blog’s owner or the service provider. If this approach is not successful, remedies such as those used in the Nextra case may also be available to affected business owners.

Friday 4 July 2014

Time to start thinking about your AGM

Although it may seem that the AGM season is still some months away, for companies with a 30 June year end, the lead up to calling the AGM is fast approaching.

Set out below are some key considerations, tips and timeframes to think about when preparing for your AGM.

For early adopters, this may have repercussions for the AGM. For example, there is now a requirement that background checks be completed on new directors with the outcome of those checks to be disclosed in the notice of meeting. If applicable, you should allow sufficient time for these checks (which may include police checks) to be completed.

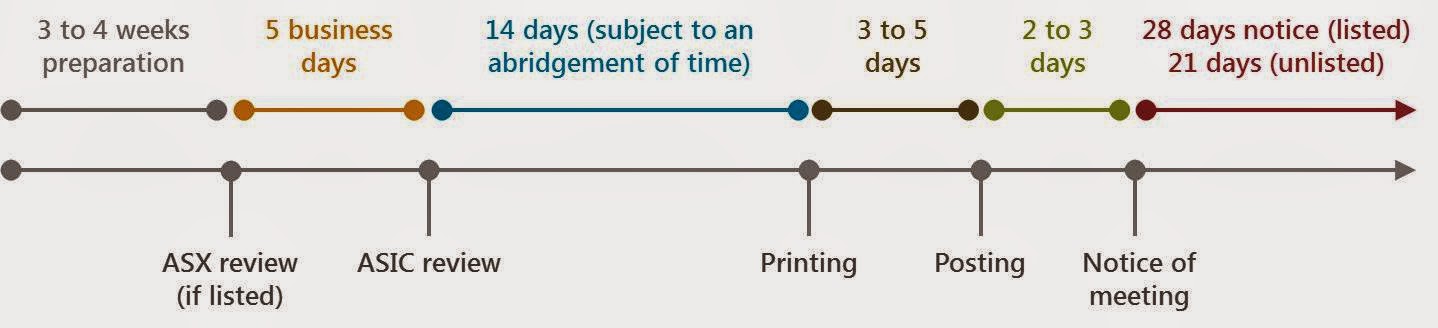

The following timeline may assist as a quick reference for the relevant steps (set out in further detail below):

Set out below are some key considerations, tips and timeframes to think about when preparing for your AGM.

Corporations Act changes

This year has seen comparatively less regulatory change. Accepted market practices have now developed around disclosure of chairman, ‘key management personnel’ and proxy voting restrictions. However, practices for meeting procedures continue to evolve (including polling on the ‘remuneration report’ and in some cases, all resolutions). You should consider your preferred approach for your AGM.New ASX Corporate Governance Principles

The Third Edition of the Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations were recently released by the ASX Corporate Governance Council as referenced in our earlier post.

Although the new Principles and Recommendations are effective from the financial year ending 30 June 2015 (for companies with a 30 June balance date), some companies are seeking to adopt the Principles and Recommendations at an earlier date.

For early adopters, this may have repercussions for the AGM. For example, there is now a requirement that background checks be completed on new directors with the outcome of those checks to be disclosed in the notice of meeting. If applicable, you should allow sufficient time for these checks (which may include police checks) to be completed.

Key steps and timeframes

The time required for preparing a notice of meeting and coordinating the mail out to shareholders is often underestimated.The following timeline may assist as a quick reference for the relevant steps (set out in further detail below):

|

| AGM timeframes - click to view larger image |

- Preparing the notice

Depending on the number of resolutions that are expected, a prudent approach is to allow 3 to 4 weeks to prepare the notice of meeting. Some possible resolutions to consider are summarised further below.

- Meeting venue

Many public companies tend to convene their AGM toward the end of November each year, which means adequate venues can be in short supply, particularly where large numbers of shareholders are expected to attend. Brisbane based companies should also be aware that the G20 Summit in November will place additional demands on venues and accommodation. You should ensure to book an appropriate venue well in advance of the preferred meeting date to avoid disappointment.

- Auditor

A company’s auditor needs to be present at the AGM and available for a reasonable time for questions from the shareholders. This means auditors will be attending a number of AGMs for other public companies in October and November. You should make arrangements with your auditor early to avoid conflicts.

- ASX review

For a listed company, it is likely that the notice will need to be lodged with ASX for review before it is finalised and posted to shareholders. ASX requires a minimum of five business days for its review.

ASX becomes particularly busy toward the final five to six weeks of the AGM season and lodging documents early will ensure that sufficient time is provided for the ASX review.

- ASIC review

Certain matters of special business, including proposed related party benefit and/or financial assistance transactions, may require the notice and other documents to be given to ASIC for review. ASIC generally has 14 days for its review.

For listed companies, an additional complicating factor is ASIC’s insistence on ‘final’ signed documents being lodged, which requires ASX’s review (5 business days) to occur before lodgment with ASIC.

- Printing and postage

Sufficient time also needs to be given for printing (e.g. 3 to 5 days) and postage (e.g. 2 to 3 days) and you should make appropriate arrangements with your share registry, public relations firm or printers (as required) at an early stage.

- Notice period

For a listed company, 28 clear days notice is required. For an unlisted company it is 21 clear days. For clear days you do not count the day of the mail out or the last day of the notice period (so, for example, 21 clear days is actually 23 days).

Resolutions

In addition to the usual resolutions (financial statements and reports, and retirement, appointment and/or re-election of directors), some other possible resolutions are:

- related party benefit and/or financial assistance approvals

- increasing the directors’ fee pool, and

- pre-approval for any termination benefits for directors or key management personnel (e.g. the issue of performance rights, where such a benefit might trigger on termination in excess limits allowed by the Corporations Act).

For listed companies, also consider resolutions for:

- adoption of the remuneration report – this resolution will vary depending on whether the company has received a strike on its remuneration report at the prior AGM

- any issue of securities above the company’s 15% placement capacity (Listing Rule 7.1) or the ratification of previous allotments to refresh this capacity (Listing Rule 7.4)

- for companies outside the S&P/ASX 300 that also have a market capitalisation of $300 million or less, whether approval is sought for the additional 10% placement capacity (Listing Rule 7.1A) - this requires a special resolution, which can only be obtained at the AGM, and

- any issue of securities to directors, which requires the approval of shareholders (Listing Rule 10.11, Listing Rule 10.14 and/or related party provisions of the Corporations Act).

Friday 23 May 2014

No news is not good news - reform of Employee Share Scheme rules

Despite industry hopes that this year’s Federal Budget would include announcements on the Abbott Government’s plans for the overhaul of taxation on employee share schemes (ESS) in Australia the Government has delayed any announcement until later this year.

It is widely considered across the industry that existing barriers to the use of employee share schemes to reward employees (particularly in Australia’s technology and innovation sector) place companies operating in Australia at a competitive disadvantage to their overseas counterparts and that removing those barriers is critical to development of the industry in Australia.

An effective employee share scheme regime allows start-ups to attract and retain talent at a time when they are cash poor. Usually for these types of companies it is simply not possible to reward staff with salary commensurate with that offered by established businesses or industries and offering any salary shortfall in equity both rewards the employee (allowing them to share in the future success) and fosters a sense of ownership and participation.

The intricacy surrounding the existing employee share scheme regime in Australia is not just a barrier to the use of such schemes for companies in the technology and innovation industries. Companies in a range of industries all across Australia are hampered by the inherent complexity in the rules.

The time at which the ESS interest is taxed may, however, be deferred in certain circumstances – most commonly, where there is a real risk that the employee may forfeit or lose the interest.

The advantage of having a small amount taxed upfront upon the grant of the options is that once this occurs, the ESS tax provisions will no longer apply. Instead, the capital gains tax (CGT) provisions will operate from that point forward. This has two benefits:

This may be contrasted with the deferral position. When deferral ends (and the discount is potentially much higher, due to growth of the business) the discount is included in the employee’s assessable income and subject to tax at their marginal rate.

Importantly, the current regime does not allow the employee to choose upfront taxation in circumstances where the conditions for the deferral concession are satisfied (although it is possible to structure schemes that take advantage of the benefits of upfront taxation at a time when the value is low).

Although the rules provide valuation mechanisms, these cannot always be used. In circumstances where the employer is not listed, the company needs to obtain a business valuation each time it wishes to issue shares to employees. Obviously obtaining valuations of many start-ups is problematic or, at the very least, expensive. Further, where incentive arrangements satisfy the conditions for the deferral concession to apply, there can be multiple valuation points, meaning significant compliance costs in obtaining valuations of the relevant interests at each time a deferral period ends for an employee.

The fact that employees are likely to be taxed upfront on the value of their shares, of itself, provides significant disincentive. Where there is no market for those shares, the employee is stuck with an upfront tax liability in respect of an unrealised (and potentially unrealisable) investment. Particularly relevant to start-ups is the risk that an employee will be left with an upfront tax liability in respect of a venture that may fail and shares that are ultimately worthless.

Even in circumstances where the employee is able to sell shares to meet any upfront tax liability the result is equivalent to paying a cash bonus or salary and the executive using the after cash amount to fund an acquisition of shares at market price. While this may well be the economic goal of the provisions, it is hardly a means to encourage share ownership.

Whilst this scenario is problematic for a listed company, it is even worse for a private company or entity in which there is no liquidity or available market to dispose of the shares. In either case, the use of employee share schemes to provide significant benefits to employees that do not qualify for the deferral concession are rare.

Although it is possible to structure an employee share scheme around the obvious complexity in the existing regime, this of itself can produce a scheme that is both costly, complex and in certain industries, may not provide employees with the incentive sought by implementation of the scheme in the first place.

Arguably, the proposals in the paper remain highly restrictive when compared to international comparisons (with which the measures are designed to compete for attraction and retention of talent). In any event, the paper focuses only on the use of employee share schemes by start-ups with the concessions proposed restricted to businesses with a turnover of less than $5 million and 15 or fewer employees meaning that concessions are effectively restricted to ‘small businesses’.

If the Government did proceed with the arrangement and sought to implement some or all of the proposals in full, there would still remain a substantive competitive disadvantage of Australia compared to other overseas incentives, such as those in the UK, US and Singapore:

It is widely considered across the industry that existing barriers to the use of employee share schemes to reward employees (particularly in Australia’s technology and innovation sector) place companies operating in Australia at a competitive disadvantage to their overseas counterparts and that removing those barriers is critical to development of the industry in Australia.

An effective employee share scheme regime allows start-ups to attract and retain talent at a time when they are cash poor. Usually for these types of companies it is simply not possible to reward staff with salary commensurate with that offered by established businesses or industries and offering any salary shortfall in equity both rewards the employee (allowing them to share in the future success) and fosters a sense of ownership and participation.

The intricacy surrounding the existing employee share scheme regime in Australia is not just a barrier to the use of such schemes for companies in the technology and innovation industries. Companies in a range of industries all across Australia are hampered by the inherent complexity in the rules.

Overview of the current rules

The default position under the current rules is that each employee who is issued a share or a right to acquire a share (ESS interest) at a discount to market value must include that discount in their ordinary assessable income and pay tax on this amount at their marginal tax rate.The time at which the ESS interest is taxed may, however, be deferred in certain circumstances – most commonly, where there is a real risk that the employee may forfeit or lose the interest.

The advantage of having a small amount taxed upfront upon the grant of the options is that once this occurs, the ESS tax provisions will no longer apply. Instead, the capital gains tax (CGT) provisions will operate from that point forward. This has two benefits:

- where the taxpayer is an individual or individual beneficiary of a trust, the CGT discount can be accessed for future increases in value (i.e. beyond that already taxed upfront under the ESS rules) subject to meeting the normal discount conditions, and

- any future taxing point will only arise when a CGT event occurs (normally when there is a disposal or other ‘cash-out’ event) and if this does not occur, deferral can be indefinite.

This may be contrasted with the deferral position. When deferral ends (and the discount is potentially much higher, due to growth of the business) the discount is included in the employee’s assessable income and subject to tax at their marginal rate.

Importantly, the current regime does not allow the employee to choose upfront taxation in circumstances where the conditions for the deferral concession are satisfied (although it is possible to structure schemes that take advantage of the benefits of upfront taxation at a time when the value is low).

Barriers to implementation

The current complexity and regulation of the rules is the most significant barrier to the wide adoption of employee share schemes in Australia. While there are some alternatives that can allow effective remuneration of key employees for start-ups or companies with high growth potential, due to their complexity (and cost) such plans are not effective to encourage broad participation by employees.Although the rules provide valuation mechanisms, these cannot always be used. In circumstances where the employer is not listed, the company needs to obtain a business valuation each time it wishes to issue shares to employees. Obviously obtaining valuations of many start-ups is problematic or, at the very least, expensive. Further, where incentive arrangements satisfy the conditions for the deferral concession to apply, there can be multiple valuation points, meaning significant compliance costs in obtaining valuations of the relevant interests at each time a deferral period ends for an employee.

The fact that employees are likely to be taxed upfront on the value of their shares, of itself, provides significant disincentive. Where there is no market for those shares, the employee is stuck with an upfront tax liability in respect of an unrealised (and potentially unrealisable) investment. Particularly relevant to start-ups is the risk that an employee will be left with an upfront tax liability in respect of a venture that may fail and shares that are ultimately worthless.

Even in circumstances where the employee is able to sell shares to meet any upfront tax liability the result is equivalent to paying a cash bonus or salary and the executive using the after cash amount to fund an acquisition of shares at market price. While this may well be the economic goal of the provisions, it is hardly a means to encourage share ownership.

Whilst this scenario is problematic for a listed company, it is even worse for a private company or entity in which there is no liquidity or available market to dispose of the shares. In either case, the use of employee share schemes to provide significant benefits to employees that do not qualify for the deferral concession are rare.

Although it is possible to structure an employee share scheme around the obvious complexity in the existing regime, this of itself can produce a scheme that is both costly, complex and in certain industries, may not provide employees with the incentive sought by implementation of the scheme in the first place.

Where to from here?

Treasury released a discussion paper in August 2013 seeking input in respect of the application of the employee share schemes for ‘start-up companies’. While the paper originally had a closing date for submissions of 30 August 2013, the consultation process was put on hold due to the Federal election and there has been no further announcement from the Government as to the proposed time line for reform of the employee share scheme regime.Arguably, the proposals in the paper remain highly restrictive when compared to international comparisons (with which the measures are designed to compete for attraction and retention of talent). In any event, the paper focuses only on the use of employee share schemes by start-ups with the concessions proposed restricted to businesses with a turnover of less than $5 million and 15 or fewer employees meaning that concessions are effectively restricted to ‘small businesses’.

If the Government did proceed with the arrangement and sought to implement some or all of the proposals in full, there would still remain a substantive competitive disadvantage of Australia compared to other overseas incentives, such as those in the UK, US and Singapore:

- in Singapore a 75% exemption is provided for up to SGD$10 million in value received by an employee over a 10 year period

- in the UK, the concession allows up to £120,000 per employee and £3 million per employer to be granted without tax and without National Insurance Contributions paid on exercise, and

- the US employee share arrangements (which are not limited to start up or speculative companies) provide for options of up to $100,000 a year per employee to be issued and stock purchase plans of $25,000 per year per employee, which are not taxed when granted or exercised. Taxation only occurs when the stock is sold and, if held for one year from the date of purchase and two years from the date of granting in respect of options, CGT rates are available.

It goes without saying that both the current and proposed employee share scheme tax incentives in Australia are substantially more restrictive and less generous than a number of our overseas peers and a full review of the regime is warranted.

It is envisaged that the Government will announce proposed changes to the rules later this year. For companies that do not have the luxury of waiting this long, there are still structures available to optimise the effectiveness of an employee share scheme and tailored advice should be sought prior to implementation.

Friday 11 April 2014

Is crowd funding an alternative means for raising capital?

Crowd funding is a concept that has existed for some time in various jurisdictions, but has only received attention relatively recently from potential stakeholders and regulators in Australia.

It has been identified as an alternative means for raising capital, in particular as a source of ‘scarce’ capital for early stage and start-up companies, from a large number of small investors. It has been used successfully and most commonly for creative projects such as music, film and mobile apps.

However, the next stage of crowd funding’s evolution, involving the issue of securities in return for funds and the accompanying regulatory framework, is still in its infancy in Australia.

Essentially, it involves advertising an idea online through an intermediary crowd funding platform (usually a website) to allow for the dissemination of the idea to a wide audience. This can result in significant funds being raised, typically in small individual quantities from a large number of participants.

The most common forms of crowd funding in Australia have been donation funding for charitable causes or pre-payment funding (an investment in return for the promise of a product or service that is produced / provided if sufficient funding is raised).

A more complex area now being considered, including in a Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC) paper in September 2013, is the concept of crowd sourced equity funding (CSEF). As with other means of capital raising, this would involve the issue of securities in return for funds. It is this that has caused the most concern for ASIC and other regulators.

ASIC has also made it clear that various crowd funding arrangements, particularly CSEF, will be caught by the fundraising and/or financial service licensing provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which could give rise to penalties for persons seeking to raise the funds and/or the operators of the crowd funding websites. Another potential consideration is whether the crowd funding amounts to a pre-purchase arrangement of a product or service (under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)).

These concerns are potentially exaggerated by the borderless nature of crowd funding, often making it available to investors in any country, so the number of affected persons can be significantly greater than with other means of fundraising. Retail investors are the most likely target, emphasising the need for proper legal protections. That said, CAMAC acknowledges that, with modest investments across a range of opportunities, the perceived risk to such investors is likely to be reduced.

This has been acknowledged in other jurisdictions, such as New Zealand, where new legislation has been introduced to facilitate CSEF, as an initiative to support early-stage and growth companies.

Some other practical considerations in seeking funds through crowd funding include ensuring compliance with the laws of applicable foreign jurisdictions (where the website is accessible) and that a bona fide website operator is used.

If CSEF does arise as a means of raising funds, a company issuing securities would also need to consider the practical implications of a potentially large shareholder base with unmarketable parcels of shares and the relevant regulatory and administrative costs which may arise.

It may take some time for more varied forms of crowd funding, particularly CSEF, to emerge in Australia, but it is certainly something to continue to watch.

It has been identified as an alternative means for raising capital, in particular as a source of ‘scarce’ capital for early stage and start-up companies, from a large number of small investors. It has been used successfully and most commonly for creative projects such as music, film and mobile apps.

However, the next stage of crowd funding’s evolution, involving the issue of securities in return for funds and the accompanying regulatory framework, is still in its infancy in Australia.

What is it?

In its guidance released in August 2012, Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) defined crowd funding as ‘the use of the internet and social media to raise funds in support of a specific project or business idea. Project sponsors or pledgers typically receive some reward in return for their funds. In some cases, the reward expected may be of minor value and is merely incidental rather than the purpose of the contribution’.Essentially, it involves advertising an idea online through an intermediary crowd funding platform (usually a website) to allow for the dissemination of the idea to a wide audience. This can result in significant funds being raised, typically in small individual quantities from a large number of participants.

The most common forms of crowd funding in Australia have been donation funding for charitable causes or pre-payment funding (an investment in return for the promise of a product or service that is produced / provided if sufficient funding is raised).

A more complex area now being considered, including in a Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC) paper in September 2013, is the concept of crowd sourced equity funding (CSEF). As with other means of capital raising, this would involve the issue of securities in return for funds. It is this that has caused the most concern for ASIC and other regulators.

Regulator concerns

ASIC has indicated that crowd funding is an area that is to come under increased surveillance, having regard to its consumer protection mandate (with concerns that persons may make an investment or payment based on limited or potentially misleading information, or possibly even fraud).ASIC has also made it clear that various crowd funding arrangements, particularly CSEF, will be caught by the fundraising and/or financial service licensing provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which could give rise to penalties for persons seeking to raise the funds and/or the operators of the crowd funding websites. Another potential consideration is whether the crowd funding amounts to a pre-purchase arrangement of a product or service (under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)).

These concerns are potentially exaggerated by the borderless nature of crowd funding, often making it available to investors in any country, so the number of affected persons can be significantly greater than with other means of fundraising. Retail investors are the most likely target, emphasising the need for proper legal protections. That said, CAMAC acknowledges that, with modest investments across a range of opportunities, the perceived risk to such investors is likely to be reduced.

This has been acknowledged in other jurisdictions, such as New Zealand, where new legislation has been introduced to facilitate CSEF, as an initiative to support early-stage and growth companies.

Next steps as an alternative means of raising capital

At this stage, there have been no indications for a change to applicable Australian law (e.g. to modify the relevant fundraising exemptions) to allow for CSEF.Some other practical considerations in seeking funds through crowd funding include ensuring compliance with the laws of applicable foreign jurisdictions (where the website is accessible) and that a bona fide website operator is used.

If CSEF does arise as a means of raising funds, a company issuing securities would also need to consider the practical implications of a potentially large shareholder base with unmarketable parcels of shares and the relevant regulatory and administrative costs which may arise.

It may take some time for more varied forms of crowd funding, particularly CSEF, to emerge in Australia, but it is certainly something to continue to watch.

Friday 28 March 2014

ASX releases new Corporate Governance Principles

Yesterday, the ASX Corporate Governance Council released the third edition of its Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations. The new principles will take effect for a listed entity's first full financial year commencing on or after 1 July 2014.

The release marks the first major revision of key Australian corporate governance principles since the GFC and follows the issuing of draft principles and a consultation process examined in an earlier post last August.

The Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations are available to view at:

http://www.asx.com.au/documents/asx-compliance/cgc-principles-and-recommendations-3rd-edn.pdf.

The release marks the first major revision of key Australian corporate governance principles since the GFC and follows the issuing of draft principles and a consultation process examined in an earlier post last August.

The Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations are available to view at:

http://www.asx.com.au/documents/asx-compliance/cgc-principles-and-recommendations-3rd-edn.pdf.

Thursday 13 March 2014

Whistleblower protection under the Corporations Act

Whistleblower protection has received a lot of media attention recently, following the Senate Inquiry into the performance of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and its alleged failure to act promptly on information provided by whistleblowers in relation to serious misconduct in Commonwealth Bank’s financial planning arm.

Consistent with ASIC’s commitment to improve communication and handling of information brought to its attention by whistleblowers, it has released a new Information Sheet (Info Sheet 52) which provides guidance on the statutory protections available to those who report misconduct or provide evidence of a breach of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) to ASIC.

The whistleblower provisions of the Corporations Act are designed to encourage people associated with a company to alert the company (through its officers) or ASIC, to illegal behaviour. Information provided by whistleblowers is considered a protected disclosure (provided certain criteria are satisfied), and must be kept confidential. Both the information provided and the identity of the whistleblower may not be disclosed, unless that disclosure is specifically authorised by law.

Generally speaking, for the purposes of the Corporations Act, a whistleblower is a person who is an employee, contractor or member of an organisation, who reports or ‘discloses’ misconduct or dishonest or illegal activity that has occurred within that same organisation. The report must be made to either ASIC, the company’s auditor or member of the internal audit team, a director, secretary or senior manager, or a person authorised to receive whistleblower disclosures (such as a Whistleblower Protection Officer).

It is imperative that companies have a whistleblower policy in place to ensure employees know how to report issues, who to report them to, and how they will be dealt with when the company is alerted.

The policy should also detail the rights of employees to disclose improper conduct on a confidential basis without fear of retaliation.

A whistleblower reporting tool (e.g. a hotline or online portal with analytical capabilities) is also a useful way to detect fraud within an organisation.

Info Sheet 52 is a useful reference tool, to ensure your policy adequately details the protections available to whistleblowers. It should, however, be noted that the protections under the Corporations Act only apply to whistleblowers who report breaches of the Act, as opposed to breaches of other laws, or the company’s internal policies.

To afford the protections under the Corporations Act, the whistleblower must identify their name when making a disclosure, have reasonable grounds to suspect that the information being disclosed indicates that the company, company officer or employee may have breached the Corporations Act and must make the disclosure in good faith.

Identifying the whistleblower is not typically required under other laws, nor is it under many internal policies. Therefore, if a matter that would result in a breach of the Corporations Act is reported anonymously through internal channels, the whistleblower would need to be identified before the matter was referred to ASIC to benefit from the protections in the Corporations Act against civil and criminal litigation.

Further, the provisions of the Corporations Act may be relied on by the whistleblower in their defence if they are the subject of an action for disclosing protected information. It is important to note that no contractual or other remedy can be enforced against the person on the basis of the disclosure.

Where a whistleblower’s employment is terminated because of a disclosure made under the Corporations Act, the whistleblower can apply to Court for an order to be reinstated in that position, or in another position at a comparable level.

The publication of Info Sheet 52 is an important reminder that whistleblowers play a role in detecting serious misconduct within organisations and should be afforded adequate protections. Companies must ensure that procedures are in place so that matters of concern that are raised can be dealt with on a timely basis, either internally or, in the case of a serious breach, by escalating the matter to ASIC or the Australian Federal Police.

Consistent with ASIC’s commitment to improve communication and handling of information brought to its attention by whistleblowers, it has released a new Information Sheet (Info Sheet 52) which provides guidance on the statutory protections available to those who report misconduct or provide evidence of a breach of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) to ASIC.

The whistleblower provisions of the Corporations Act are designed to encourage people associated with a company to alert the company (through its officers) or ASIC, to illegal behaviour. Information provided by whistleblowers is considered a protected disclosure (provided certain criteria are satisfied), and must be kept confidential. Both the information provided and the identity of the whistleblower may not be disclosed, unless that disclosure is specifically authorised by law.

Generally speaking, for the purposes of the Corporations Act, a whistleblower is a person who is an employee, contractor or member of an organisation, who reports or ‘discloses’ misconduct or dishonest or illegal activity that has occurred within that same organisation. The report must be made to either ASIC, the company’s auditor or member of the internal audit team, a director, secretary or senior manager, or a person authorised to receive whistleblower disclosures (such as a Whistleblower Protection Officer).

It is imperative that companies have a whistleblower policy in place to ensure employees know how to report issues, who to report them to, and how they will be dealt with when the company is alerted.

The policy should also detail the rights of employees to disclose improper conduct on a confidential basis without fear of retaliation.

A whistleblower reporting tool (e.g. a hotline or online portal with analytical capabilities) is also a useful way to detect fraud within an organisation.

Info Sheet 52 is a useful reference tool, to ensure your policy adequately details the protections available to whistleblowers. It should, however, be noted that the protections under the Corporations Act only apply to whistleblowers who report breaches of the Act, as opposed to breaches of other laws, or the company’s internal policies.

To afford the protections under the Corporations Act, the whistleblower must identify their name when making a disclosure, have reasonable grounds to suspect that the information being disclosed indicates that the company, company officer or employee may have breached the Corporations Act and must make the disclosure in good faith.

Identifying the whistleblower is not typically required under other laws, nor is it under many internal policies. Therefore, if a matter that would result in a breach of the Corporations Act is reported anonymously through internal channels, the whistleblower would need to be identified before the matter was referred to ASIC to benefit from the protections in the Corporations Act against civil and criminal litigation.

Further, the provisions of the Corporations Act may be relied on by the whistleblower in their defence if they are the subject of an action for disclosing protected information. It is important to note that no contractual or other remedy can be enforced against the person on the basis of the disclosure.

Where a whistleblower’s employment is terminated because of a disclosure made under the Corporations Act, the whistleblower can apply to Court for an order to be reinstated in that position, or in another position at a comparable level.

The publication of Info Sheet 52 is an important reminder that whistleblowers play a role in detecting serious misconduct within organisations and should be afforded adequate protections. Companies must ensure that procedures are in place so that matters of concern that are raised can be dealt with on a timely basis, either internally or, in the case of a serious breach, by escalating the matter to ASIC or the Australian Federal Police.

Thursday 27 February 2014

The new Australian Privacy Principles – Is your organisation compliant?

On 12 March 2014, fundamental changes to Australian privacy laws will take effect. The changes introduce new rules about how organisations collect and store personal information. With penalties up to $1.7 million enforceable for serious breaches, organisations must act now to ensure compliance.

As part of the privacy law reform process, the Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection) Act 2012 (Privacy Amendment Act) was introduced to Parliament in May 2012 marking significant changes to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (Privacy Act).

The changes to the Privacy Act include a new set of harmonised privacy principles that regulate the collection and handling of personal information called the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) applying to most organisations who turn over $3 million or more annually, and to Commonwealth Government agencies. The APPs will replace the National Privacy Principles that apply to businesses and the Information Privacy Principles that apply to Government agencies.

To some extent, the APPs are based on the existing privacy principles but now impose additional obligations on organisations when dealing with personal information. In particular, the APPs require organisations to provide additional discloses in their privacy documentation and internal procedures and policies ensuring the protection and ongoing quality of personal information that they use and store.

APPs are legally binding principles and aim to be the cornerstone of the privacy protection framework in the Privacy Act, by setting out uniform standards for dealing with personal information. The APPs are structured to reflect the personal information life cycle and are grouped into five parts, including:

Under the Privacy Amendment Act, the Information Commissioner receives new powers to seek civil penalties of up to $1.7 million from organisations who commit serious or repeated breaches of privacy. The Information Commissioner may also conduct ‘own motion’ privacy investigations on organisations without first receiving a privacy complaint from a member of the public.

The Privacy Amendment Act also implements changes to credit reporting laws, including the introduction of more comprehensive reporting about an individual’s current credit commitments and repayment history information. The credit reporting changes are also supplemented by a new credit reporting code.

While the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner has released APP guidelines to assist organisations with the transition to the APPs (which must occur on or before 12 March 2014), it will be interesting to see how and when the Information Commissioner exercises its new powers in relation to privacy compliance. Under the APPs, it will therefore be important for relevant organisations to consider their existing information policies, review and update their privacy documents and develop internal procedures to ensure compliance by 12 March 2014.

As part of the privacy law reform process, the Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection) Act 2012 (Privacy Amendment Act) was introduced to Parliament in May 2012 marking significant changes to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (Privacy Act).

The changes to the Privacy Act include a new set of harmonised privacy principles that regulate the collection and handling of personal information called the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) applying to most organisations who turn over $3 million or more annually, and to Commonwealth Government agencies. The APPs will replace the National Privacy Principles that apply to businesses and the Information Privacy Principles that apply to Government agencies.

To some extent, the APPs are based on the existing privacy principles but now impose additional obligations on organisations when dealing with personal information. In particular, the APPs require organisations to provide additional discloses in their privacy documentation and internal procedures and policies ensuring the protection and ongoing quality of personal information that they use and store.

APPs are legally binding principles and aim to be the cornerstone of the privacy protection framework in the Privacy Act, by setting out uniform standards for dealing with personal information. The APPs are structured to reflect the personal information life cycle and are grouped into five parts, including:

- the consideration of personal information

- collection of personal information

- dealing with personal information

- integrity of personal information, and

- access to, and correction of personal information.

Under the Privacy Amendment Act, the Information Commissioner receives new powers to seek civil penalties of up to $1.7 million from organisations who commit serious or repeated breaches of privacy. The Information Commissioner may also conduct ‘own motion’ privacy investigations on organisations without first receiving a privacy complaint from a member of the public.

The Privacy Amendment Act also implements changes to credit reporting laws, including the introduction of more comprehensive reporting about an individual’s current credit commitments and repayment history information. The credit reporting changes are also supplemented by a new credit reporting code.

While the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner has released APP guidelines to assist organisations with the transition to the APPs (which must occur on or before 12 March 2014), it will be interesting to see how and when the Information Commissioner exercises its new powers in relation to privacy compliance. Under the APPs, it will therefore be important for relevant organisations to consider their existing information policies, review and update their privacy documents and develop internal procedures to ensure compliance by 12 March 2014.

Friday 14 February 2014

ASIC takes ‘no further action’ on David Jones’ alleged insider trading

Whilst some commentators have intimated the buying of shares by two company directors just three days before the release of price sensitive sales results was on the limits of insider trading laws, ASIC has decided to issue David Jones with a ‘no further action’ letter. Despite ASIC’s decision to not take further action, the share trading has still resulted in the resignation of the relevant directors.

On 10 January 2014, less than two weeks after ASIC announced its conclusion of the two month investigation, accused directors, Steve Vamos and Leigh Clapham, and David Jones Chairman, Peter Mason, have announced their decision to resign from David Jones as part of a ‘board renewal process’. This news comes after significant pressure from shareholders to remove the directors, despite the fact ASIC’s investigation yielded no evidence to prove that the trades were made in violation of the insider trading laws.

The investigation was sparked after criticism emerged following the alleged approval of share trading by two non-executive directors, just three days prior to the release of unexpected positive sales results, and one day following David Jones receiving a scrip merger proposal from industry rival Myer. The directors, who bought a total of 32,500 shares were said to have made the trades to illustrate their long-term commitment to the company. This was said to be because CEO, Paul Zahra, had announced his intention to resign earlier that month under suggestion there were disagreements between various board members.

Peter Mason, who allegedly approved the trading, claimed the directors were not privy to any price sensitive information. Yet his defence became unhinged after both announcements caused share prices to spike significantly, despite the merger announcement also stating the proposal was rejected. Mason allegedly still claimed the directors did not previously obtain the quarterly sales data and that the merger was not materially price sensitive. If it was found the directors did not have the quarterly sales information and the merger proposal did not satisfy the definition of materially price sensitive information, the directors would not have violated the insider trading laws (amongst other possible defences).

For ASIC to successfully prosecute an instance of insider trading, investigators must be able to satisfy four key tests, proving: the directors actually possessed the information at the time of trades; the information was inside information that was not generally available; the information was price sensitive; and the suspected directors knew, or ought to have known, the information was material and not publicly available.